© the lowry collection, salford

Shape without form, shade without colour,

ts eliot – the hollow men, part I

Paralysed force, gesture without motion

poet slash bum

laurence stephen ‘ls’ lowry was a rent collector and artist known best for his urban landscapes peopled with half-unreal human figures, and dogs. his serendipitous back-of-the-envelope pencil sketches on serviettes, cloakroom tickets and, er, envelopes, now sell for thousands of pounds.

thomas stearns ‘ts’ eliot was one of the twentieth century’s greatest poets. for his ‘outstanding, pioneer contribution to present-day poetry’ he was awarded the 1948 nobel prize in literature. he was also an essayist, publisher, playwright, literary critic and editor. he was, by most accounts, quite good at those things too.

greig burgoyne is a scottish artist who works with film, live performance, installation, sound, and text. his work utilises self-imposed rules and processes, and explores seemingly contradictory ideas relating to absence and nothingness, visualising the invisible, performative actions, and play.

and me? i am a poet slash bum. i am a freelance writer. in other words, i write for free. in this post i bring my considerable inexperience to bear upon the distinguished aforementioned artistic trio. i am by no conceivable measure qualified to do so. i am not an art historian. i am not a lowry scholar, or an eliot scholar. i know nothing. and so…

towwsafm

in march 2023, i visited the lowry, the steel-clad neo-guggenheimy theatre-cum-gallery complex at salford quays, to check out the permanent collection of lowry’s work, and by pure chance, came across greig burgoyne’s temporary exhibition of newly commissioned work, the one who was standing apart from me.

towwsafm comprised a series of videos, performances, and ‘floor and wall-based works’, all against the backdrop of lowry’s majestic pencil drawings, rescued by the artist himself from a skip round the back of the gallery, aka ‘the archives’.

i didn’t attend with the intention of writing an essay about the exhibition. i didn’t even know there was going to be an exhibition. i absolutely, definitely didn’t read the exhibition catalogue.

but a year later, i still sometimes think about it, so here are my thoughts.

a year ago

the title of the piece is ‘buzzing’.

buzzing, or as you’ll hear it here, ‘int’north’ – buzzin’ – means excited, exciting, or excellent. lowry was a manchester painter – the manchester painter – a beloved ambassador of the city, a symbol, like batman, or superman. manchester’s official symbol is the worker bee. it seems appropriate.

the artist, greig burgoyne, is a normal-looking guy with a normal haircut, normal glasses, normal tshirt, normal shoes, and a normal megaphone.

he is sounding a strange, incoherent drone into, or perhaps out of, this megaphone; prancing, as he buzzes, pseudo-randomly around the small square space, hopscotching from flower to flower, like a demented dancing bee. the floor is haphazardly littered with an indeterminate number of large, lightly footprinted sheets of sturdy black cardstock, and what appear to be the scrunched-up remnants of the rest of their number.

the drone stops. the artist stops. he puts down the microphone. steps slightly to one side of the piece of paper on which he most lately landed, and picks it up. he screws it up into a ball. puts it down. he picks up the megaphone. the drone starts again.

as is inevitably the case with these infinite-loop video installations, i arrive in media res. i see middle, end, and then beginning. now the normal-looking man with the normal-looking megaphone is standing in the same white-walled space, but the screwed-up balls are miraculously flat again and have been rearranged into a grid. he brings the megaphone to his mouth.

i watch the whole thing again. this is hilarious, i think. and brilliant. all this comedy, chaos, absurdity, even profundity, emerging from a set of rules so simple they can be explained in seconds. the floor is lava. move around and make a funny sound. when you run out of air, whichever piece of paper you end up on, screw it up, and go again. like a kid’s game. like a game a kid would invent, bored, because that’s what bored kids do. an only-child sort of activity. single-player musical chairs for those without friends or furniture.

what does it mean? does it mean anything? the component pieces of the work seem so pointedly mundane, so resolutely unremarkable. maybe the megaphone symbolises something? who can shout the loudest. purposeless noise. television static. transmitting, re-transmitting. the sound of the early universe, before there were ears to hear it. nonesense in and nonesense out. a tale | told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, | signifying nothing. maybe, maybe not.

what interests me most about this piece though, is the idea of arbitrary self-imposed rules, or what the artist refers to as ‘process-led, rule-based strategies.’

freedom is slavery.

all art is defined by limitations, and our responses to those limitations define us as artists.

artistic limitations can take many forms. they can be personal, determined by our own limited ability – to do, to think, to imagine. they can be cultural or societal, determined by our own, and other people’s prejudices. they can be economic.

they can also be self-imposed.

self-imposed limitations are found in all areas of art. take film for example. these limitations can be stated explicitly, as in the prescriptive cinematographic dogma of terrence malick and emmanuel lubezki. or they can be understood implicitly, as a back-construction from the film itself. watch tree of life – what’s there, and what’s not there? there are any number of tightly constrained stylistic decisions relating to the look, the sound, the editing, the mise-en-scène, the feel of a film – even the dialogue. consider [this] iconic example from the tv series the wire, where two detectives, mcnulty and bunk, solve a murder only using variations on the word ‘fuck’.

often, artistic works that push the boundaries of what was previously thought possible, that seem to be the most ingenious, or radical, are based on strict self-imposed limitations.

and it’s not just in film, but in literature, in music – in any artistic category. lowry himself limited his palette to five colours only in all of his paintings – ivory black, vermilion, prussian blue, yellow ochre, and flake white.

once you start thinking about it, you realise that making art without any limitations is actually impossible. you’ve got to start somewhere. you’ve got to have some way of going from everything to something, from infinite possibility to the picture on the page. at the absolute minimum you’ve got to say, i’m going to write this, or draw this, or sing this, or dance this, or i’m going to write, draw, sing and dance this.

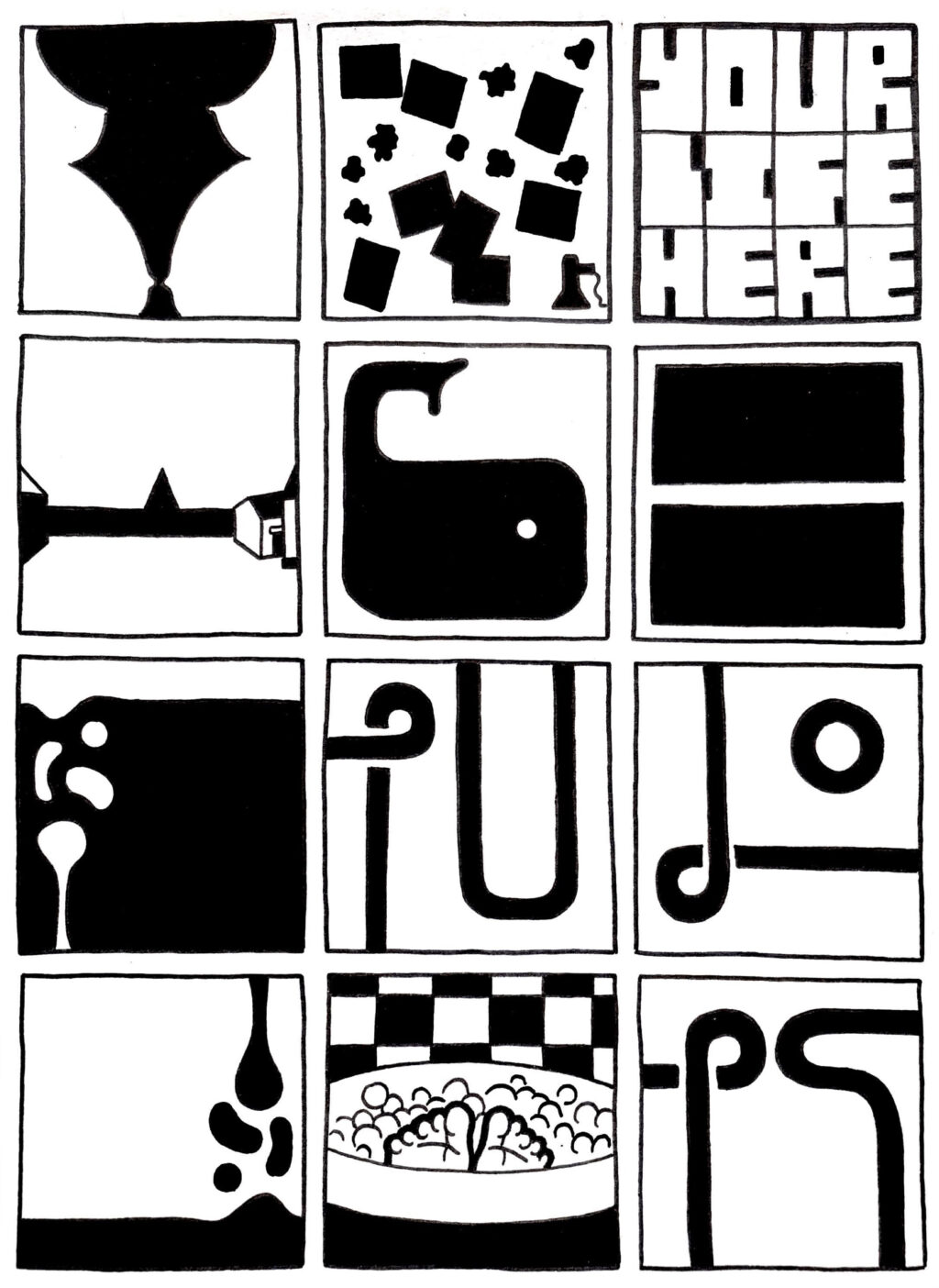

i start all my street-art panes by drawing a 4×3 grid in black 0.5mm fineliner onto a piece of white a5 cartridge paper. that’s my starting point. that’s my mote of dust, my sticky something about which other individually-barely-existent microscopic particles can begin to agglomerate.

self-imposed limitations allow you, as an artist, to do anything, are necessary to do anything, even if your limitation is just – i’m going to sit here and wait for inspiration.

purposefulness without purpose

then again, most self-imposed limitations are not arbitrary. more like artistic manifestos. they are choices made with the clear expectation of some specific end result – a predefined, predictable (to an extent) end result. you might even call it a style. they are a means to an end, whereas an arbitrary limitation, or constraint, is more like the reverse.

an arbitrary constraint is applied without any end in mind. it doesn’t point to something, or reach for something. it isn’t teleological in intent. it’s the difference between knowing where you want to be, and knowing where you are. it’s an eye-closed globe-spinning finger-pointing life decision.

burgoyne uses the phrase purposefulness without purpose, which i think perfectly describes arbitrary constraints. arbitrary constraints are purposeful. they are deliberate. they are a deliberate spanner in the metaphorical works. but they are without purpose in the sense that they do not aim to arrive at a known destination.

again, the arts abound with completely, or incompletely arbitrary constraints.

do nothing for as long as possible, do the washing up, take a break, just carry on, turn it upside down, make an exhaustive list of everything you might do and do the last thing on the list. these are examples from musician brian eno and artist peter schmidt’s oblique strategies, a set of gnomic suggestions, aphorisms and remarks for breaking creative blocks.

raymond quineau, co-founder of the oulipou group, who practice arbitrarily constrained writing, such as avoiding the use of certain common letters (lipograms), described oulipians as ‘rats who construct the labyrinth from which they plan to escape‘.

frequently, the more apparently free the artistic form, the more arbitrary the constraints imposed upon it by practising artists. graffiti writing, for example, is an art form so ostensibly lawless it’s literally illegal. here is a description of the creative process of the graffiti artist ECO:

Graffiti writing is central to the way Eco draws. Often when he sketches it is with the endless and infinite brief of writing his name ECO/EKO/EKOE. ‘The brief set down many years ago by graffiti innovators – this is my baseline and from there I only have my own preconceptions of what a letter is to stop me going anywhere I like… weight, form and line, anything that isn’t a letter has its beginning with me as a letter, is abstracted till it becomes something else, a pattern, a nonentity, a character.’

Eco – Street Sketchbook

burgoyne, too, uses all sorts of self-imposed, seemingly arbitrary constraints.

but why? why make it hard for yourself? why play five-a-side footie with a piece of confetti? why not just use a football, like normal people?

why make rules? isn’t art about breaking rules?

well, when you work with arbitrary constraints, instead of creating the universe, you create the conditions for the universe to create itself:

you set the initial state, and you define the laws of physics.

the rules of the game.

that way, you get to surprise yourself.

you get to enjoy the show, like everybody else.

you get to play along.

you get to watch it all unfold, in real time. like a performance.

shape without form.

i think that might be part of what burgoyne means by ‘the performative nature of drawing’, one of the themes of his work generally, and of this exhibition in particular.

the performative nature of drawing

this exhibition features several of lowry’s pencil drawings, chosen by burgoyne himself. but what, if anything, is ‘performative’ about lowry’s drawings? or what does the ‘performative nature of drawing’ have to do with lowry?

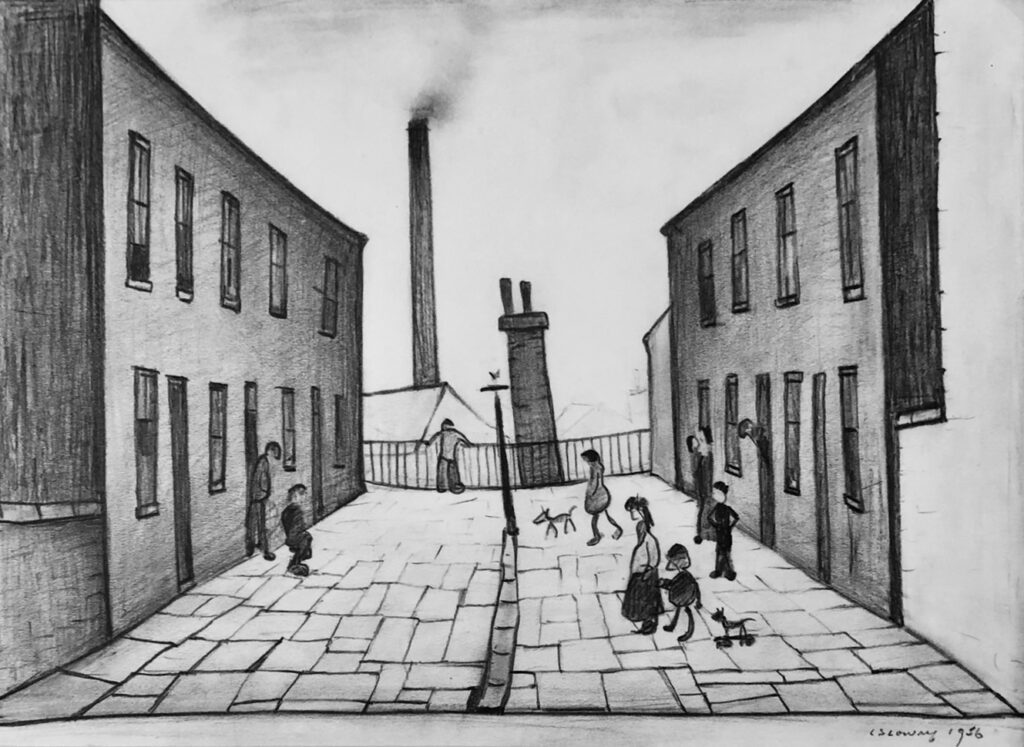

on the surface, not much, though i love his drawings. and i love that the exhibition featured them so prominently, because they are absolutely my favourite part of his ‘oover. i love the subjects and scenes he selects. i love their melancholy playfulness, the masterful shading, the smoky thumb-smudged skies, the bold lines, the clean minimalism.

but lowry was not, to my knowledge, a performative person in the sense of being dramatic, pretentious, or self-promoting. he lived and worked in pendlebury. he holidayed in sunderland. he made his living as a rent collector, painting by night, while he lived with and looked after his bed-bound mother. he turned down an OBE, a CBE, and a knighthood. he was hardly damien hurst.

so what gives?

performative acts or behaviour are intended to show how a person wants to be seen by others, rather than who they really are. lowry was a storyteller. he was a secretive and mischievous man who enjoyed stories irrespective of their truth. his anecdotes were more notable for humour than accuracy, and in many cases he set out deliberately to deceive.

in preparation for the exhibition, burgoyne explored the gallery when it was empty (of people), focussing not on what is present, and seen, but what is absent and sensed. if we consider what is absent from lowry’s drawings, we might see them as performative. so what’s absent? what’s sensed?

well, for one thing, the drawings themselves. lowry’s pencil drawings are often unfairly overlooked in favour of his more famous oil paintings. they are brought out in rotation, like second-class citizens, to spend a limited time in the luculent splendour of the limited gallery space. yet lowry himself didn’t think of his drawings as unfinished preparatory pieces for forthcoming paintings, but as separate standalone works. so by bringing them up from the basement, burgoyne brings to our attention one of our blind spots when it comes to lowry’s work. when you choose to see one thing, you choose to unsee another.

unknown to his friends and the public, lowry produced a series of erotic works that were not seen until after his death. these ‘mannequin sketches’ or ‘marionette works’ depict a mysterious female figure, the same ‘ann’ who appears in other portraits and sketches produced throughout his lifetime, enduring a succession of sexually charged and humiliating tortures. art critic richard dorment wrote that these works ‘reveal a sexual anxiety which is never so much as hinted at in the work of the previous 60 years.’

so lowry was, in some ways, a performer in life, and perhaps also in art. but i think there’s more. consider this definition of performance, in the context of performance art:

Performance is not (and never was) a medium, not something that an artwork can be, but rather a set of questions and concerns about how art relates to people and the wider social world

Jonah Westerman

taking that definition, it’s easy to say, well, then everything is performative. but if everything is performative, if every action is an act, a performance, then what does it matter? here’s why:

There are these two young fish swimming along and they happen to meet an older fish swimming the other way, who nods at them and says “Morning, boys. How’s the water?” And the two young fish swim on for a bit, and then eventually one of them looks over at the other and goes “What the hell is water?”

David Foster Wallace – This Is Water: Some Thoughts, Delivered on a Significant Occasion, about Living a Compassionate Life.

as dfw points out – the most obvious, important realities are often the ones that are hardest to see and talk about. if everything is performative, if we’re all just poor players strutting and fretting, then we ought to at least attempt to remember what’s real, and what’s not. society isn’t real. money isn’t real. real numbers aren’t real.

life, like drawing, is a performance.

lowry workout

or: performance art, and the art of watching performance art

not only do i find myself at this exhibition by accident, but i accidentally find myself at this exhibition on its opening weekend. apparently there is to be a ‘performance’. we, that is me and the rest of what will soon comprise the ‘audience’ arrange ourselves carefully around the performance space. we spread ourselves flat against the formerly important gallery walls, as far away from the empty space in the middle as we can get. now our focus is floor, not walls. we’re back to front, we’re inside out. some sit, some stand. a pregnant pause. we all wait for something to happen.

in the round (or in this case, the square), everyone is a performer. performers performing the role of performers; audience members performing the role of audience members. the performers know the rules, but the audience doesn’t. they know how to act, as it were, but we don’t.

the performers shuffle awkwardly in, and take their places in the centre. they are wearing rough, handwoven hessian sacks, which cover their entire bodies, head to trainered toe. they begin to move. not the frenetic fluttering of burgoyne in ‘buzzing’, but a very slow, very deliberate dance. like the slowest, most avant-garde flash mob ever. it’s not sluggish though. it’s not careless. every movement is almost painfully careful, like each one means something, like each one matters. i think of the cautious many-legged choreography of a male tarantula, or praying mantis, desperately attempting to get laid but not eaten.

it’s library quiet. and as this bunch of anonymous bags step, shift and sway in extreme slowmotion around the makeshift performance space, ahead of me, two people turn slowly, silently, surreptitiously towards each other, share an expression that says ‘what the fuck’ and swallow grins. i smile too. is it supposed to be funny? is it ok to laugh?

i like it a lot.

watching performance art can be an uncomfortable experience. a performance requires an audience, and as part of the audience, you inevitably become part of the performance. you become willingly or unwillingly complicit in something. it’s like being dragged along to a bank robbery. you feel bad about shooting that guard, sure, and those bystanders, and that cop, but man, what a fucking ride! what a thrill! and think of the money. performance art can be confusing, disturbing, even morally questionable. it can be funny. it can be all of those things, and the best, frequently is.

burgoyne’s performers, i find out later, are imitating the body language of lowry’s figures, simulating the stereotyped gestures of his matchstick men.

however, what occurs to me while watching the performance is not any painting of lowry’s, but some lines of poetry by ts eliot. the hollow men, which, or maybe whom, i first came across in francis ford coppola’s visionary vietnam epic, apocalpse now.

We are the hollow men

We are the stuffed men

Leaning together

Headpiece filled with straw. Alas!

Our dried voices, when

We whisper together

Are quiet and meaningless

As wind in dry grass

Or rats’ feet over broken glass

In our dry cellarShape without form, shade without colour,

Paralysed force, gesture without motion;Those who have crossed

ts eliot – the hollow men, part I

With direct eyes, to death’s other Kingdom

Remember us-if at all-not as lost

Violent souls, but only

As the hollow men

The stuffed men.

the hollow men

eliot’s hollow men, and coppola’s apocalpse now, are linked, inextricably, via joseph conrad’s heart of darkness. both owe their very existence to the novella. eliot’s hollow men has as its epitaph a line from heart of darkness – ‘Mistah Kurtz – he dead’. that’s the selfsame kurtz, now walter e. and a colonel in the u.s. marine corps, played by marlon brando, who recites the lines above in coppola’s apocalypse now.

the hollow men follows the otherworldly journey of the spiritually dead. they are empty men, lost, broken souls whose only hope is death. they fail to transform their motions into actions, conception to creation, desire to fulfillment.

but who are they really?

they are the brainless scarecrow before he meets dorothy. the twenty-first century schizoid man. the u.s. marines in vietnam. the sackcloth shufflers in burgoyne’s performance piece.

they are the wage slaves. the factory workers of lowry’s manchester. the office workers of today’s. the interchangeable machine components. the perfect products and the perfect consumers. the ghostless shells. the phone zombies. the cattle-truck commuters. the pulsing maggot mass of humanity. they are us.

the stuffed men

1922, the year when ts eliot’s the waste land was published, was also the year in which L.S. Lowry painted one of his first works to receive wider recognition, [A Manufacturing Town].

these two pieces – eliot’s poem, and lowry’s painting – are unflinchingly bleak depictions of life out of balance. by the time they died, both men had lived through two world wars. the world, their world, saw the mechanised slaughter of almost an entire generation of young men in the trenches, and the attempted extermination of an entire race in the holocaust. they saw evil. they saw apathy. they saw the worst of humanity. they saw what conrad saw in the belgian congo – the horror, the horror.

lowry, too, a pendlebury rent collector, had front row seats to another smaller-scale shitshow, as the once mighty manchester dismantled its mills, and sent their former inhabitants scurrying around like woodlice from under an upturned stone. he observed, and bore witness, as the first and greatest industrial city in the world, declined, fell, and then somehow kept going.

lowry’s pictures are often full of people occupying large open spaces. however, burgoyne’s interest is in the space around the figures, their absence rather than their presence. ‘stuffed’ therefore is an interesting word, in this context. it means both empty and full (of nothing). it also means fucked.

howard jacobson, a manchester-born novelist, echoes these same thoughts about the presence, and absence of humanity in lowry’s cityscapes – his ‘paintings of scurrying humanity’ – describing them as ‘landscapes of isolation’, an isolation that lowry saw in the world, and in himself.

They are all essentially, in my view, paintings without people in them, even when there are people in them; all – whether they contain gravestones or symbolic crucifixes or not – landscapes of isolation.

Howard Jacobson – The Proud Provincial Loneliness of LS Lowry

[Lowry] said he painted what he saw, but he also said he painted what he was, and what he saw was what he was – a humanity with nowhere in particular to go, nowhere that made any sense anyway; a humanity on no errand of any consequence, driven hither and thither by desires it barely recognised as its own.

lowry’s matchstick men, his hollow men, his stuffed men, his ‘scurrying humanity’ cast no shadows. they are there, but also not there. they are ‘wind in dry grass’ and ‘rat’s feet over broken glass.’

I wanted to paint myself into what absorbed me … Natural figures would have broken the spell of it, so I made my figures half unreal. Some critics have said that I turned my figures into puppets, as if my aim were to hint at the hard economic necessities that drove them. To say the truth, I was not thinking very much about the people. I did not care for them in the way a social reformer does. They are part of a private beauty that haunted me. I loved them and the houses in the same way: as part of a vision.

LS Lowry

Shape without form, shade without colour,

Paralysed force, gesture without motion

these two lines of eliot’s poem are, to me, the essence of burgoyne’s exhibition. the quintessence. the quiddity. the leftover boiled-down black stuff at the bottom of the pan. apparent contradiction. absence and presence. the invisible and the visible. that which is seen, and that which is sensed. the performative nature of everything.

purposefulness without purpose

indeed, the word ‘gesture’ features several times in the exhibition description. the idea of paralysed force, of gesture without motion is the basis of one of the other videos – Rock/Et – in which burgoyne repeatedly attempts to enact a pose from The Painter on the Road to Tarascon, by van gogh, the ‘master of gesture and mark-making.’

gesture implies motion, just as shape implies form. any attempt to separate, to isolate them seems doomed to fail. and yet, that might be the point of it all. the mystery. the paradox.

and as i can’t hope to put it better myself, here’s howard jacobson again, masterfully summing it up:

For the most part these matchstick figures hurry off the canvas, the forward slope of their bodies suggesting not just dejection, or the bad weather that is partly instrumental to that dejection, but a sort of propulsion disconnected to their wills, some going left, some going right, the difference in direction their only distinguishing characteristic, but no reason, really, why those going left shouldn’t be going right, and vice versa.

Dwarfed by the mills, the chimneys and the chapels, they are foreground without function, the very peremptoriness with which they’re drawn – for why would one reduce the various and abundant fleshiness of humanity to a matchstick silhouette? – the proof that their individuality is not what matters to Lowry. They are a crowd, a cluster, a congregation, viewed by someone who is not of them – not contemptuously or satirically, but from somewhere they are not – figures of loneliness themselves, congregating and yet separate, a mystery to the painter. And that’s the subject – not their street-corner, ragamuffin heritage vitality, and not their servitude to capitalism – but their mystery.

Inscrutable bustle is what he sees; a many legged, faceless interference in the real scene as it concerns him, the landscape proper, which has no one in it. His figures were painted in order to be imagined away, until at last they were literally imagined away in the triumphantly painted seascapes where Lowry can pursue what always absorbed him as a painter most – the blank infinity of things.

Howard Jacobson – The Proud Provincial Loneliness of LS Lowry

‘the blank infinity of things.’ i mean, damn. i must remember to steal that sometime.

human(ity) after all

lowry was a mostly solitary and private person. he never married. but he knew love. his [portrait of ann] is proof enough. it is just gorgeous.

his drawings and paintings, to me at least, suggest someone with an absolute love of being alive. of being in this world. in this place and time, of all possible places and times. the humour, humanity, and heartbreaking drama of a hundred or more humdrum human-scale accidents. the cosmic awe of a mountain range at night. from his ant-farm cityscapes, to his intimate street scenes, like [a fight], and [man lying on a wall]; from his brooding, darkly surrealist [a landmark] and [lake landscape], to his magisterially minimalist [seascape] – all are spectacular facets of a mind grappling with the miraculous implausibility of it all. the sheer statistical improbability. the near impossibility.

he also knew depression. in my opinion, lowry’s grotesque self-portrait [head of a man] is one of the most compelling depictions of despair ever painted. seeing it in person, staring into those big, blue, blood-rimmed eyes is, for me, to experience a sort of profound recognition. here is someone who got it. who understood. who knew. who went there, and who brought something back.

it’s so easy to despair for humanity, after all

joseph conrad did and ts eliot definitely did and francis ford coppola did

and maybe greig burgoyne did, or does

and ls lowry did, i think

but not completely

because all of them found some reason not to.

what was that reason?

i once overheard a conversation that went like this:

– where are you going?

– to my grave, man. to my grave.

we’re all going to die. one way or another, we’re all headed straight for our graves. i think lowry felt despair sometimes. for himself and for humanity. who doesn’t? if you’ve ever lived in manchester you’ve felt it too, stood on a freezing platform waiting for the bolton train that’s an hour late already and probably not even going to show up at all, because why would it, on some shit, rainy day, after two weeks straight of shit, rainy days.

lowry described manchester as ‘this drab city’. and yet there must’ve been something about it. and there still is – i’m convinced of that. i’m not sure even he knew exactly what it was, or is, but he spent a lifetime trying to figure it out. i don’t think he ever gave up. hope’s like that. unscientific, unreasonable, and unexpected.

it peeps out like a pair of knackered black nike air maxes from under the hem of a hand-stitched hessian sack.

postscript:

if you’re interested in ls lowry, loneliness, and manchester (and who isn’t?), i highly recommend howard jacobson’s [lecture] – the proud provincial loneliness of ls lowry. i read it while – let’s call it ‘researching’ – this post, and immediately regretted doing so, because it says exactly what i wanted to say, but better. but whatever, you’ve read, or scrolled, this far already, so now see how it should be done.

and of course, if the best thing isn’t your thing, there’s always manchester’s number-one beatles tribute band. and [the masterplan] is actually one of their best songs, it’s everything oasis do best, done best, and the video, an animation based on lowry’s style, which specifically references a bunch of his paintings, is pure dead brilliant.

post postscript:

late, late in the long, long process of writing this, as i was thinking about depictions of the hollow men, i remembered a section of the 2021 stop-motion adult animated experimental horror film – mad god. written, produced, and directed by onetime dinosaur supervisor phil ‘you had one job’ tippett. it’s a profoundly disturbing masterpiece, something like wallace and gromit meets dante’s inferno, on bad, bad mushrooms. i love it, and intend to plug it relentlessly some other time. but for now, for anyone wanting to dive deep, it features a sequence in which a seemingly infinite number of pathetic straw people are spat out from some sort of straw people birthing machine, and made to toil and moil for the rest of their short, miserable lives, on a vast, incomprehensible construction project (which is pretty much what doing a phd feels like). remind you of anything? i find it’s best not to think too hard about these things.